‘Nature takes on an order for us says Cézanne, not because it has one, but because we make one up. Representing is intervening. A picture, to be true to life, ought to be full of the sense that things could have been otherwise.’ T. J. Clarke, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present.

Three months or so ago I started reading art historian T J Clark’s extraordinary book on Cézanne, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, published in 2022. I finished it a few days ago. I’m not exactly sure how I came to read it but I’ve been feeling bored with my reading for a while and I had an intuition it might help. When I say bored with my reading, I don’t mean I’m bored by what I’m reading (or not usually) but that my own patterns of interpretation have become stagnant, my style of readings - procedures, questions and so on - have become too predictable. I’m bored with how I read.

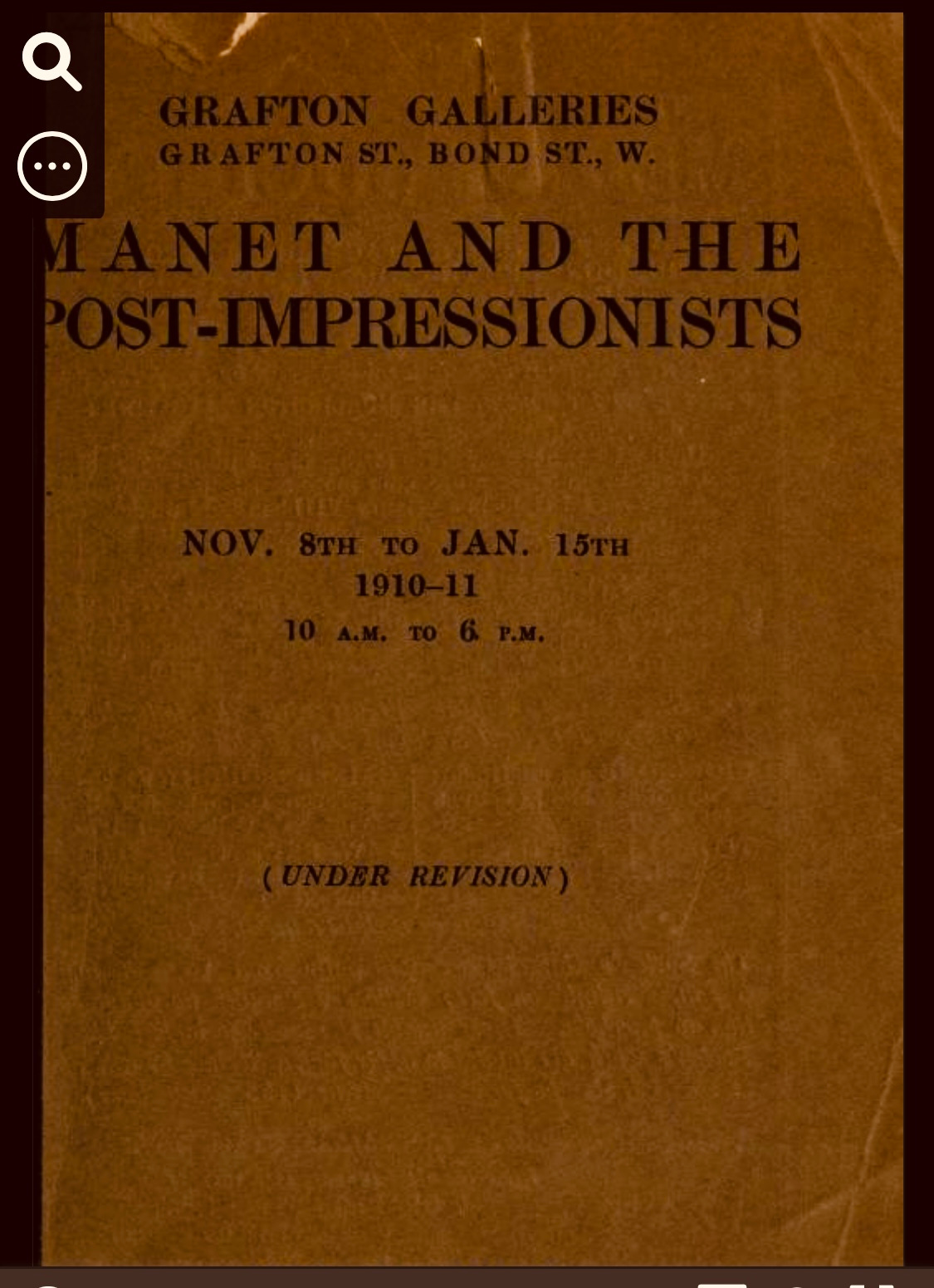

But Clark didn’t arrive as a possible answer from nowhere. This year I’ve been reading a lot of modernist and writing. And I keep coming across writers who obsess about Cézanne - Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett and Katherine Mansfield to name just three. I think of Mansfield visiting the Roger Fry-organised Grafton Street Gallery exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists in London in 1910 as I worked through the catalogue (link below) and was reminded of just how inter-medial modernist experimentation in writing was. Mansfield also worked as a contributor and editor of the short-lived magazine Rhythm which fused contemporary art and writing.

Many years ago as a literature student I had read Clark’s early book about Impressionism, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, and I still remember his chapter about Manet’s Olympia and ‘the scandal of class’.

Reading Clark on Cézanne has been one of the most exciting critical experiences I’ve had in years (though I don’t go out critically as often as I did). Clark sets himself the task of exploring the profound, paradoxical strangeness in Cézanne: a brilliant, breathtaking vividness - this apple, this hand, this crystalline rock face - yet all that life lies just out of reach.

As a writer and teacher from another medium, I was fascinated by Cézanne‘s practice. He learns so much through his ‘imitation’ of other painters - Clark discusses his relationship with Pissarro - a standard learning practice for artists but Cézanne does something extraordinary with it. Imitation is a practice and form of knowledge which touches the boundaries between them but also shifts the original horizon of possibilities.

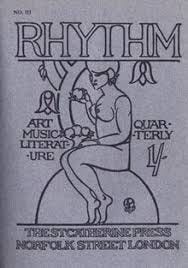

Cézanne paints the same objects over and over, the same landscapes, the same groups of human figures. He uses the same piece of printed fabric in any number of still lives, makes numerous paintings of card players. The setting, number of players and observers change, so does their orientation within the painting as a whole. The symbolism of the game changes, as does the foregrounding of the symbolic reading itself.

I’m curious about how writers incorporate deliberate, studied imitation in their practice. I’ve never studied creative writing formally and I would love to know how imitation works in such a context. Clark describes the general practice of making copies of another artist’s work as ‘free translations’ , ‘never intended to be faithful’, which is tantalising as translation is a concept I’ve been thinking about because of my (super slow) progress through KateBriggs24. Reading Barthes on the haiku in The Preparation of the Novel, at one point, I stopped noting down haiku characteristics and started writing companion haikus. What is the difference between my notes and my (bad) haikus?

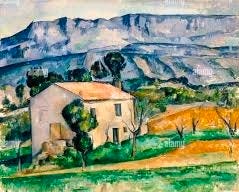

But Clark sees a different practice in Cézanne’s imitation of Pissarro, a act of submission, ‘it wished to enter into Pissarro’s way of seeing and doing things’ but couldn’t quite, the divergences or ‘failures’ have their own coherence, their own ‘aesthetic dignity.’ One of the things Cézanne‘s paintings do is to mess up and disturb foreground and background, focus and peripheries. As you look at his paintings, different elements link and untie. A house in a landscape is at once bound to its environment, made out of the same stuff (the line of a wall shared with a tree, a chimney blurring into a cloud) and resolutely not of it, or perhaps not any more What does it mean for a translation or a translating or reading context to be/come visible and then invisible again? I need to finish Kate Briggs’s This Little Art.

If These Apples Should Fall is also fascinating for the methods that Clark himself uses. No doubt some of these are ‘just’ what art historians do but to me it is extremely suggestive for critical writing.

Clark keeps freeform notes on the various viewings he makes of a painting which he initially treats as separate. Often he starts a viewing by following and then noting the pattern of his attention and interest. It’s not that each viewing is discrete - how could it be - but he tries not to rush for a single interpretative key or to close down interpretative possibilities. Years of teaching preparation (where do we need to be by the end of this class, module etc) and trying to read too much too quickly seem to have sapped me of the pleasures and excitement of living in a reading where you can proliferate interpretations without ordering and sequencing them to quickly.

Inspired by If These Apples Should Fall, I’ve been rereading a single story by Katherine Mansfield, ‘The Man Without a Temperament’, taking notes each time about where my attention travels, what catches my ‘eye’. I’ve probably read it 20 times or so over the last couple of months. Am I forcing a connection between Cézanne and Mansfield, because of her interest in his painting, because of the circumstance of my own reading? Perhaps. But Cézanne’s ‘I see in touches’ or, as Clark translates it, ‘by touches. I see by means of coloured marks. I see by making them.’ Ignoring the cliché of Mansfield’s painterly style, her desire to find ways to write the experiencing of things seems to me to draw them together. I might write more about reading Mansfield next time.

Grafton Street Gallery. Catalogue for Manet and the Post-Impressionists, 1910